As part of its farm gate pricing system review, Murray Goulburn is studying the way farmers are paid overseas, including in New Zealand. So, how are Kiwi dairy farmers paid for their milk and what are the pluses and minuses of the NZ system?

I’m very grateful to Andrew Hoggard, the National Dairy Chair of NZ’s peak farmer body, the Federated Farmers, for writing this explainer post for us.

In New Zealand there is no “one” way that the milk price is calculated, we have many different companies.

Fonterra is obviously the largest at around 78% of milk supply, but you also have two other Co-ops, and then several private processors, the largest of which is Open Country Dairies.

Generally, in most countries the unwritten rule is that the largest Co-op in the market sets the milk price.

In New Zealand’s case that is Fonterra, while the other Co-ops will return all profits they make (after any retentions) back to the farmers as milk price, so they sit outside that rule to a degree.

The private companies will pay a price based on the Fonterra price, so it might be a few cents more to attract supply, or a few cents less to retain supply.

Often the way these companies have attracted supply is through the fact that farmers can leave Fonterra, sell their Fonterra shares which for most farmers is a tidy sum, and then get a similar milk price supplying someone else and use that capital for something different.

So, in a practical sense, the Fonterra milk price is often viewed as the New Zealand Milk Price. Fonterra was created as a result of the two largest Co-ops merging with the NZ Dairy Board back in 2001.

The Government passed special legislation to bypass the Commerce Commission (our version of ACCC). This legislation, the Dairy Industry Restructuring Act (DIRA), set many rules that Fonterra had to follow to allow for domestic competition and transparency.

This led to the development of the milk price manual. In the early days the manual was slightly different to how it works now, with the Global Dairy Trade are a key component of it these days.

That said during the Dairy Board days, we have always had a system of forecast payout, advance rates, retro payments, and final payout.

This system continues today with most companies in New Zealand following the milk price manual and that methodology for calculating the payout (for Fonterra).

How does it work for Fonterra farmers?

At the start of each season (June) Fonterra will advise stakeholders what the forecast payout for the season will be.

This is essentially a speculative assessment as to where the market is heading. In announcing the forecast payout, they also reveal the advance rate and payment schedule (see link to schedule below).

advance-payment-rates-single-season-181120161

Something also unique to New Zealand, which the rest of the world perhaps does not follow, is all bills are expected to be settled on the 20th of the month, for the preceding month.

Today, I’m writing this on February 20, so I’m being paid for all the milk I produced in January.

The Advance rate is the amount I will be paid in the first months of the season; this is usually 60-70% of the forecast payout.

The schedule then shows how that advance rate lifts throughout the season. For example, today I am being paid $4.20 as the advance rate for all the milk that was produced in January, is worth $4.20.

Now the previous month the advance rate was $4.15, that was all the milked produced to the end of December. Thus this month I also get a retro payment of five cents on every kg of milk solids produced up to the end of December.

Next month the advance rate lifts to $4.30, so every kg produced in February will be paid at $4.30, and then I will get 10 cents on every kg produced up until the end of January.

So basically, every time that the advance rate lifts then I get a retrospective payment for all the milk produced up to that point to ensure that everything produced until that point in time has been paid at the advance rate.

If the Board of Fonterra however, at any time during the season feel that the forecast needs to be altered, they will do so and amend the schedule.

Should the payout have to be revised down then they may well scrap several lifts in the advance rate. Very rarely as this occurred in New Zealand where a company has had to claw back payments from a farmer.

That’s why we have a lower advance rate than the projected payout, so that if the market turns, you don’t end up taking money back off farmers. Kiwi farmers don’t get upset by much, but claw backs would have us reaching for our pitchforks!

When the season ends on May 31, the full payout is still outstanding at that stage, with retro payments due in June, July, August and September, with final payment in October.

This provides a good cashflow over the dry period. It also helps the company in making all the final sales and collecting payments for that season’s products.

Calculating payout

The milk price manual sets the benchmark. Basically, it takes the prices from the Global Dairy Trade, for a basket of commodity goods, heavily weighted for WMP.

The manual determines what a hypothetical, efficient competitor to Fonterra, might be able to pay for raw milk and still make a dollar, using a mixture of Fonterra’s actual data around transport and manufacturing costs along with some assumed costs. That’s effectively your milk price.

Any margin that Fonterra makes above that then goes into a Dividend, which because it is a Co-op then goes back to the farmers.

This way the farmer gets to see what the base value of their milk is worth, and can be responsive on-farm to changes in the world milk price. The Dividend otherwise shows me how good my Co-op is at adding value to my milk.

If these two streams were bundled together, you would have to assign a hard-core forensic accountant to pick through the annual report to work out how well the Co-op is doing.

For example, if it was bundled together and we had a milk price of $7.50, we might think cool, everything is sweet, but that could just be that the raw milk is worth $7.45, and the Co-op is only adding five cents.

Whereas unbundled, you would see that straight away and start asking some hard questions. Likewise, if we got a milk price of $4, but a dividend of $3.50, some may blame the Co-op for the milk price.

But in actual reality they should be doing high fives for the excellent dividend, and for not pushing any milk production because it’s not worth it.

Ideally every Kiwi dairy farmer should be trying to base their system on being profitable on the milk price alone. Because the dividend isn’t a financial reward from how well you look after your cows, it’s from investing your co-op.

One other key point in New Zealand, no one can jump ship mid-season. At around this time of the year you advise your company if you are staying with them for next season, though some of the private companies have three to five year contracts.

What you do find here is that we don’t have much in the way of chopping and changing between milk companies, compared to Australia.

Alternative Payout Models

Two independent New Zealand co-ops differ from Fonterra through combining the milk price with a dividend. Synlait and Miraka offer premiums for farmers who operate their farms on best environmental practice. But they still use the schedule like Fonterra.

The only real point of difference exists with Open Country, who have three payment periods, and the prices vary over those periods, with usually the final period at the back end of the season having a higher price.

In terms of managing risk, we have recently had the launch of milk price futures here in NZ, it is still in its infancy, and farmers will need to be very carefully in using these tools.

Some companies have also offered a guaranteed milk price, where they match a customer wanting a certain amount of product at a certain price over a time period, and farmers willing to take that price.

However, probably the best way to manage risk is to be aware of what’s happening. That’s why so many Kiwi farmers pay attention to the fortnightly GDT auction, because that trend we know will show up in our milk price.

Other things to watch are the world markets, will President Trump’s proposed ‘Border Wall’ hurt American milk production, increasing demand from Mexico for other suppliers.

Generally, we are at the mercy of geopolitics when it comes to milk prices, while domestically the politics involve on-farm rules and regulations, which also impact on the milk price. Being aware of something before it hits should enable you prepare better for it.

One obvious thing in Australia to watch will be the New Zealand milk price, because of our greater exposure to world markets we will respond to big shifts in supply and demand quite quickly in terms of milk price.

Australia ultimately does follow, as your domestic market will only insulate you for a short period of time. Anyone that claims different probably studied trade theory at Trump University.

New Zealand has long standing Free Trade Agreements with Australia, thus there will come a point if either of our domestic milk prices get too far removed from one another, the reality is that dairy products will move across the Tasman, and even out prices.

There are plenty of economic theories that back up that assertion. If you view the New Zealand milk price as clear de-facto for the world price, then simply applying the NZ/AUS exchange rate to that will tell you the value of the milk in your vat is worth on the world market.

The Aussie price might not exactly match that but it will follow it. I think the key thing to remember, no one owes you a living just because you’re a farmer. You are a businessperson, you need to recognise your own risks and have plans for dealing with them.

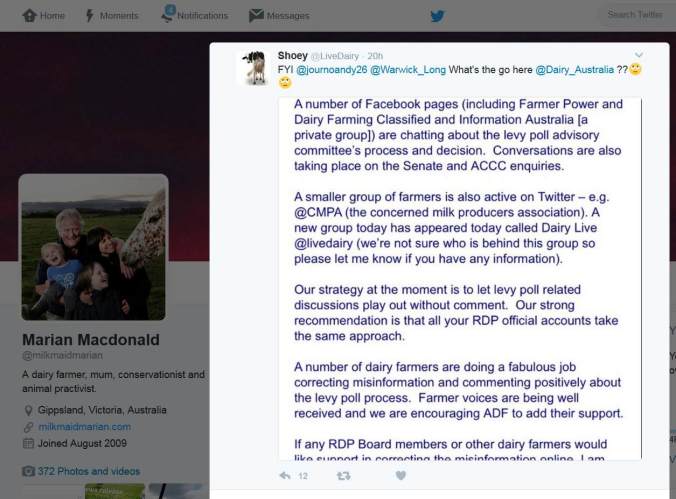

Thanks very much to Andrew Hoggard, National Dairy Chair, Federated Farmers, for explaining the NZ farm gate milk price system so thoroughly. Milk Maid Marian appreciates your generosity!